This Scarred Land: New Mountainscapes.

Made entirely in Himachal Pradesh, the series of landscape photography is remarkable documents of the hand of man on what was ‘Dev Bhumi’ – a sacred land. Instead, we are presented with a vision of a scarred land, where man and machine are gouging the earth on a Himalayan scale. These are no landscapes of Nainsukh or Roerich – vistas of romance or mystical power. The Himalayas were most memorably photographed by Samuel Bourne in the 19th Century. The famous photographs of the Himalayas by Samuel Bourne made in the 1860s were inspired by the visual traditions of British landscape seeing. Bourne was discovering the English landscape in India – a way to seduce the colonisers into thinking that a homely familiarity could be found here.

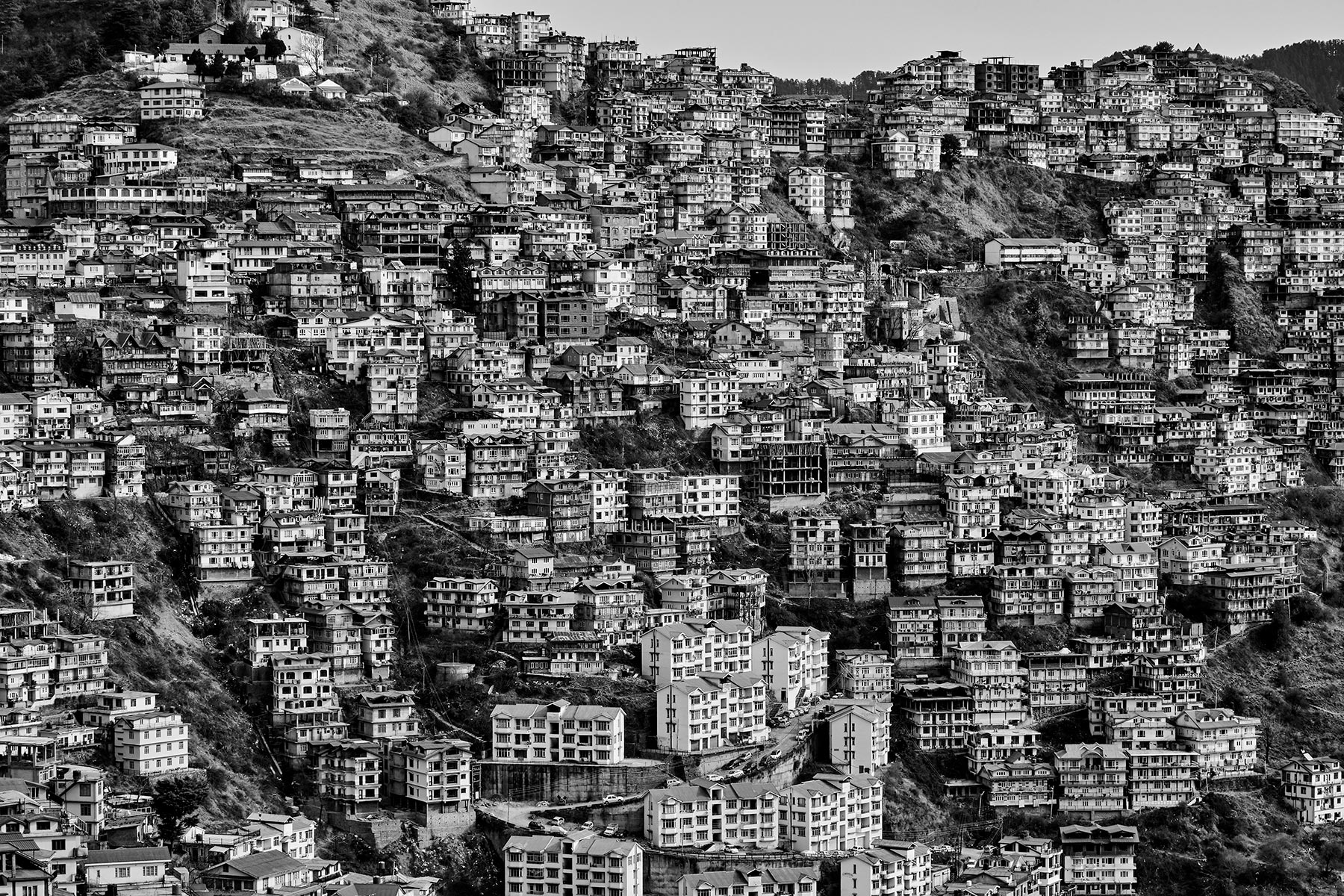

The collection of these photographs are update on those pristine vistas. These are seen through the eyes of a cool modernist using the tool of the still camera. Inspired by the photography of Samuel Bourne I have chosen to document the pristine beauty with scars of industrialization.

The Himalayas have been loaded with symbolism in our culture – the abode of Shiva, the source of the sacred rivers – all goddesses. These were the icy heights into which the Pandavas retreated after the end of the great war. Romanticised by Kalidasa, visited by the Beatles and by thousands of pilgrims every year.

When photographers extensively photographed the new industrial construction in India in the 19th century – bridges, railroads, ports - it was a part of the colonial enterprise – the development of a new colony to be settled and exploited. The photography of the new industrial projects after independence in the Nehruvian modern moment – the dams, steel factories, coal mines, railroad factories done by photographers like Sunil Janah or Ahmed Ali – were suffused with the positivism of the new India. These images were constructing the new nation – in which the worker and the peasant were heroes in the Soviet-inspired Five Year Plans.

Being a photographer of generation Y my attempt was to see India through a different lens. There is a new criticality which eschews easy emotional traps. These photographs are also in richly toned black and white – avoiding the easy seduction of colour. The reductiveness and abstraction of the black and white image reinforce the stark and almost beautiful post-industrial landscapes which are the Himalayas now. The misty vistas are clouds of dust from landslides caused by road building. The roads themselves scar in poetic loops over rocks and pasture. No human being is visible, only the marks of their enterprise. This is the poetry of India now; India that is welcoming post apocalypse, standing on the entrance of dystopia.